Sunday, December 31, 2017

EU/NI PEACE PROGRAMME 1995-99

As the Irish border is back in the news, thanks to the folly that is Brexit, I thought it an opportune moment to share some reflections on the first EU Peace Programme which covered the full area of Northern Ireland and the border counties of Ireland (South!).

The programme was sort of up and running when it hit my desk in early 1996. It had been approved by the EU on 28 July 1995 following years of work and the proximate catalyst of the 1994 ceasefires.

The basic rationale of the programme was to encourage the economic and social development of Northern Ireland as a means of cementing peace in the longer term. The emphasis in the programme was on cross-community and cross-border activities, the latter attempting both to compensate border areas for their artificially enforced peripherality and to improve north/south relationships.

I should nail my colours to the mast at this point and say that, despite many, and some justified, criticisms of the programme, my view is that it was a spectacular success.

It is important to distinguish this first Peace Programme from its successors. This one was pathbreaking in many respects while its successors both had something already in place to build on and in the normal course of such matters became more structured and bureaucratised. PEACE I (and II) were funded from across the EU structural funds, each of which also had its own protocols and regulations.

The Name

I don't know just how the Peace Programme got its name but there is a rumour that the initial working title was Special Northern Ireland Programme for Economic Recovery.

If that was the case, it clearly got nipped in the bud as soon as it was reduced to an acronym.

Canary Wharf

I was just in the process of taking over the southern end of the programme when the IRA ceasefire blew up in Canary Wharf in London's docklands. This was a huge shock to the system and it looked like curtains for the programme.

But I remember Inez McCormack from ICTU reporting to a subsequent Monitoring Committee meeting that, while new cross-community contacts were out of the question for the moment, those that had been established before the breakdown were holding. This was very encouraging.

North vs South

The northern and southern sides had significantly divergent views in how they approached implementing the Peace Programme, and this most particularly regarding EU oversight and control.

As far as the northern side was concerned, they viewed funding essentially coming from London rather than Brussels and they resented the EU Commission telling them how to spend it and holding them to account after the event. The UK was a net contributor to the EU budget, so it was their money that was involved.

In contrast, the southern side was a net beneficiary from the EU budget and we more readily accepted the Commission's right to "interfere" in the programme's implementation. We didn't always go the whole hog with them but we put up with a lot to get our hands on the dosh.

You can see echoes of the northern attitude in the current goings-on over Brexit if you look hard enough.

I should mention another difference between north and south which impinged to some extent on the operation of the programme. The locus of responsibility for the programme in the civil service was in the Department of Finance and Personnel in the north and in the Department of Finance in the south.

That may seem on the surface like a perfect match but the northerners were always conscious of an additional layer lurking in the background. Ireland is a sovereign state and deals directly with EU Councils. Northern Ireland is a regional administration and responsibility for EU affairs ultimately lies with the UK, which is the EU Member State. Responsibility at the UK end ultimately rested with the Department of Trade and Industry.

This was less of a problem in the actual implementation of the programme as opposed to its negotiation but it was often lurking in the background.

Spend, Spend, Spend

Another tension arose from within the EU structures themselves. Once a budget and a multi-annual spending profile had been agreed, the relevant section in the EU Commission saw itself on the line to deliver, so they were constantly putting pressure on the Irish, north and south, to spend up to the "targets".

In some ways this was understandable as funding for the programme had been hard fought for at EU level and leaving part of it unspent would not reflect well on the Commission.

However, in the prevailing environment in the north and the border counties it was not always easy to identify projects on which spending could be subsequently justified.

And there's the rub. However much the relevant Commission section was happy to see money spent, and however much they leaned on the authorities to spend it, their say-so was a poor defence when the financial control side of the Commission subsequently arrived to inspect and audit the books. Their judgement was completely independent of all that went before and the national authorities were on their own here.

And even if that hurdle was overcome you then had the EU Court of Auditors arriving on the warpath to flush out every hint of possibly "unjustified" expenditure to feed their bureaucratic empire-building campaign. You really couldn't win.

Product versus Process

To add to all of this, there were strong views on product versus process. There was a bit of a bricks and mortar mentality in the Commission, particularly at the financial control end. By this I mean they liked to see physically measurable results - in other words, a product.

The northern authorities also shared this attitude to some extent.

But this exercise was as much about process as product and this was much less measurable in any truly relevant sense. You could count up the numbers of cross-community projects, or even meetings, but eliciting their true meaning and potential sustainability boiled down to subjective, albeit informed, judgement.

Administrative Peace and Reconciliation

As far as process goes, I didn't myself have direct experience of it on the ground at the level of individual projects, but I did experience it at the level of those running the programme.

For example, I had no real experience of dealing with northerners at official level. My experience of the north consisted of (i) spending a holiday in Bangor when I was small, when post-war rationing was still in force and when the comic strip of Mandrake the Magician in the local paper was some six months ahead of the Dublin Evening Mail, (ii) passing through the north going to and coming from Donegal, and (iii) making an LP with Tŷ Bach in Billy McBurney's studio in the centre of Belfast.

Now I was dealing not only with my counterpart in the northern Department of Finance and Personnel but with officials from other northern departments and with implementing organisations and NGOs from both sides of the border.

There was some perceptible rapprochement there over the period when I was involved in the programme. I even got to a stage of informality which allowed me, at a conference we were organising in Ballybofey in Donegal, to welcome the northern participants to Ulster. I must say, it took most of them a few moments for that one to sink in.

As far as the central authorities and the NGOs were concerned, I think a mutual understanding slowly developed of where the other side were coming from and that it was possible for both sides to be operating in good faith.

A Lesson in Geography

A significant feature of the programme, at least for those administering it, was the Monitoring Committee meetings being held in different locations, alternating between both sides of the border.

The Monitoring Committee was not just an academic exercise after the event. It was a quasi-cross-border implementing authority where the major players were held to account in real time. It was co-chaired by the north and/or south depending on which side of the border the meeting was taking place.

I was the southern chair and Jack Layberry from NI DFP was the northern chair. We held our first Monitoring Committee meeting in the Folk Park in Omagh. I'm sure there is some symbolism lurking there but I haven't yet fully figured it out.

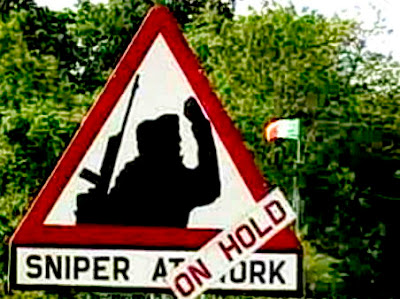

The full significance of holding meetings on alternate sides of the border may be lost on the current generation of young people. I know that one member of my staff became quite nervous as we crossed the border heading north and didn't relax until we crossed it again on the way back.

Some people saw our chairing of the Monitoring Committee as involving a conflict of interest as the Department of Finance in the south and the Department of Finance and Personnel in the north were the locus of funding and control within our respective administrations. I can understand such a view and might have sympathy with it in other circumstances. In this case I think the Committee was chaired in a reasonably objective manner and a similar situation still pertains with the Special EU Programmes Body (SEUPB) alternatively known as Boord O Owre Ocht UE Projecks.

A Roman Conspiracy

At one stage I got very alarmed when I heard that Ian Paisley claimed that the programme was a sham and the Catholics were getting all the money.

I wasn't the only one worried by this claim and a study was quickly commissioned to find out if it was true.

Our alarm escalated to defcon panic status when the study reported that it was indeed true. The Catholics were not getting all the money but they were getting a hell of a lot more than the Protestants.

Was this another potential death blow for a programme that was supposed to be promoting cross-community cooperation and inclusiveness?

Well, further research turned up some very interesting results.

It appeared that both Catholic and Protestant applications had the same rate of success (phew!) but that there were far more applications from the Catholic than from the Protestant side. So the programme itself was not biased. There was no papal conspiracy. The programme simply reflected one of the underlying features of the society of the day.

The reason for the disparity in applications seems to have arisen because Catholic communities were more organised on the ground, having been in a minority and having had to fight all the way for anything they ever got, while the Protestant communities were under the illusion that their own were looking after them anyway and so didn't need to be pressured to do so.

These results, in my book, certainly validated the politico/class analysis advanced over earlier decades by the likes of Michael Farrell.

Good Friday

Former US Senator George Mitchell, who chaired the talks leading to the Belfast Agreement in 1998 has said that "the European Union played a part in thawing relations between the Republic and Britain, which enabled the peace process and was central to the Good Friday Agreement".

The Peace Programme was clearly a significant element in this process.

Consider Michel Barnier who is currently the European Commission’s chief Brexit negotiator. He has a long history in both French national and European politics. He was EU Commissioner for Regional policy from 1999 to 2004 and as such gained good insight into the legacy of PEACE I and the Belfast Agreement of 1998.

He has said that the programme “is one of the very important instruments that has contributed towards the Good Friday agreement”.

Sadly, continued funding of the programme is in jeopardy if the UK sticks to its Brexit red lines.

Here We Go Again?

Labels:

eu,

Northern Ireland,

Peace Programme

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

Goodness, Paul, I never realised that you were such an integral part of the Peace Programme. Silly me!

ReplyDeleteLife is full of surprises.

ReplyDelete