Sunday, January 19, 2020

MY IRISH MoLI

This was MoLI's first symposium and it was held in tandem with one of its current exhibitions with a similar title.

This is what I would call a slow museum. You need to slow your pace and your head or you'll be through it in five minutes and wonder what it was all about.

The promoters have done their work and now you have to do yours. It's a slow immersion job - multimedia and interactive.

I'd recommend setting a full half day aside for a visit.

It's a great concept and I'm looking forward to seeing it in action over time.

But it's not just a static museum. You can explore the website to see the extent to which it is intended as a proactive resource, particularly for developing an awareness and practice of literature in young people.

Simon is the museum's Director and he has the right background and openess for this mighty job.

He gave us the background to the project which was ten years in the making.

He also hinted to me that there might be a place for Gordon Brewster beyond the two cartoons in the current exhibition.

You can get a bit more on Simon and the project here.

Margaret (UCD) and Katherine (NLI) are the curators of the current exhibition which draws extensively on the archives of their two institutions.

This, however, is only the tip of the iceberg as they have both been part of the driving force behind the project all along.

Katherine has been involved with this project for a long time now, and she conveyed the sense of how thrilled she was when it came to fruition and she finally entered the finished premises.

She pointed out the advantages of the modular structure of the main exhibition spaces which, while it imposes its own discipline, gives a great degree of flexibility in moving items around and in rotating exhibitions.

She instanced some of the exhibits in the current exhibition which she has curated with Margaret.

Unsurprisingly, what hit me most was the use of some of Gordon Brewster's cartoons from the National Library's wonderful collection. Brewster captures marvelously the geist of the zeit when it came to censorship and the nation's resistance to the flow of filth coming from across the water.

The Campaign against Evil Literature was not confined to stemming the flow of English Filth, it extended to some of the harmless writing of our own, as seen in the other exhibition downstairs on Kate O'Brien.

While there was a mighty struggle going on in the new state on this subject, particularly in the 1920s, the results were to be felt over the next forty years, during which even George Orwell's 1984 was banned for its sexual content. Sweet Jesus.

Katherine's phrase "The sublimated eroticism of prurience" says it all.

Margaret talked a bit about the museum's content. You'll have gathered from its logo and acronym (Molly to you) that James Joyce plays a central role, though the museum ranges far and wide through Ireland's literature, both in the museum itself and in its outreach.

The jewel in the crown is the very first edition of Ulysses itself, the famous “copy no.1” which was donated to the National Library by Harriet Shaw Weaver, a Joyce patron and editor, in 1952. Now enshrined, so to speak.

Michael gave a fascinating talk on the early days of the Irish Foreign Service, starting in 1919 as the "State on the Run" (or the counter-state as it was known) pulled out all the stops to get a hearing at the Versailles Conference.

Although this did not get the desired results from the Conference, there was a lot of progress registered then and subsequently in countering the portrayal of us by the British as a crowd of primitive wasters.

Useful contacts were also being cultivated with foreign leaders and diplomats which would later prove useful when we were looking to join the League of Nations.

The pic above is the Irish delegation setting out to make their case to the Versailles Conference (George Gavan Duffy, Seán T O'Kelly & his wife Kit Ryan).

Michael's general message was that we had a very sophisticated and worthwhile foreign service, the more so when you read the primary sources, as he does.

Vivien has a reputation as a Joyce scholar but she couldn't have been further away from this in her contribution.

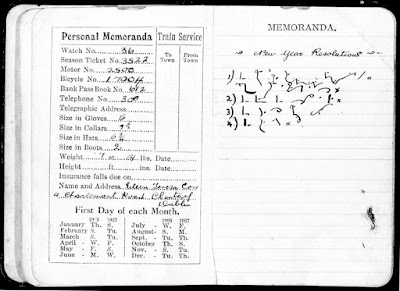

She was bringing us the contents of the 1926 diary of Eileen Corr, a sixteen year old girl. If I picked up an oral comment from someone else correctly, Eileen was Vivien's mother.

This proved an interesting exercise in writing a hitherto unknown person into history. This has been a major feature of the Decade of Commemorations and is changing our view of history. A significant part of this has been the "rediscovery" of the significant and indispensable part played by women in every aspect of our history.

Regina brought in the Irish language element of the writing.

For all the lip service paid to the Irish language, it is a source less drawn on when it comes to writing up history, particularly in the English language.

There are, of course, exceptions and three spring readily to mind: Eugene Hynes's book on the Knock apparitions, where the language in transition plays a major role; Margaret's own spectacular book on the Maamtrasna Murders where the transition takes centre stage; and Cormac Ó Gráda's writings on the Famine, where whole areas would be left out were this source to have been ignored.

However, Regina is here concerned with litríocht na Gaeilge as such. This has suffered badly from being a minority interest from the word go.

She took us through the travails of An Gúm the new state's Irish language publishing house. Many sub-standard Irish books passed muster just because they were in Irish and translations of the classics were undertaken despite English language originals, or English translations, being readily available to an English speaking population.

I was amused to hear that Máirtín Ó Cadhain's translations showed a measure of originality which eventually got him sacked by this conservative publisher. It was Sáirséal agus Dill and not An Gúm which published Cré na Cille.

I'm reading their story at the moment and finding it very disturbing. Seán & Bríghid were real patriots and pioneers and were treated disgracefully by the Department of Education. Full marks to their children, Cian and Aoileann, for documenting all of this in such a page turner.

But back to Regina, she concluded that despite its many faults, An Gúm did in some sense pave the way for the flowering of Irish language literature in later years.

I was mildly disappointed that she didn't mention Cathal Ó Sándair's Gaeilgeoir detective, Réics Carló, which I enjoyed reading during my schooldays.

I have some personal experience of transitioning from the old Cló Gaelach (the catechism with the old form "r" and "s") to the new Cló Gaelach (most of my school text books) and eventually to the Cló Rómhánach (with Stair na hEorpa) which might as well have been written in Welsh on first encounter.

What I never realised, until Regina described it, was the bitterness of the political struggle between exponents of these two rival typefaces, the Cló Gaelach and the Cló Rómhánach in the early years of the state.

The Cló Gaelach had been adopted by nationalist Irish speakers and writers in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries as a badge of Irish identity, and they were reluctant to abandon it in the new state.

The Free State Government, for whatever reason, were determined to enforce a switch to the Cló Rómhánach. This made some economic sense, as it was not every printer who carried the Gaelic fonts.

In my day I think the school originally had only a choice between two printing houses, Cahills and Irish Printers, when it came to Irish language copy. Though Regina reminded us that newspapers regularly carried features in the Cló Gaelach and might just have been available for jobbing.

While I was listening to Regina, it occurred to me to wonder if there had ever been such a thing as a Gaelic typeface typewriter. This would have had to deal not only with the fadas (acute accents on the vowels above), but with the séimhiús (lenitions/dots on most of the consonants).

When I raised this, it appeared that nobody present had ever seen such a thing, but Michael Kennedy said he had seen Garda reports which must have been done on such a machine.

I Googled it when I went home. Not only had there been such machines from a variety of manufacturers but they all used the same ingenious dead key technique as had Hely's when they adapted my own manual typewriter for the fadas in the 1970s.

On today's computer (Windows) you get the fada by pressing the vowel and the AltGr keys simultaneously, an option not possible on a manual typewriter.

This is the keyboard layout on the Underwood model. I have shaded the dead keys yellow. You can follow this up here.

This is a Conradh na Gaeilge Gaelic typeface machine from 1905.

It might be an idea for MoLI to get its hands on one of these.

Lisa rounded off the symposium with a talk on the materiality of all this stuff. This boiled down basically to design.

She touched on the greening of the red letterboxes which in mosts cases left the British royal insignia intact.

Then designs from Catholic Truth Society pamphlets, which, if you ignore the contents, are not bad. Bet you're wondering what they advise you to do on a date. You'll just have to ask them. I never read that one and the old ones are generally no longer available outside the DCU archive.

I remember one myself called Handy Answers which I wish I'd kept.

This one is a bit drab, but I suppose they didn't want to make it too exciting.

My favourite, which Lisa didn't show, is Hell. This was the stuff of those days when the church tried to scare the shit out of you as part of its play in claiming your soul for itself.

Mind you, this one does have a Joyce connection when you remember the school retreat in Portrait of the Artist. I'm hoping to work some of that into a presentation for next Bloomsday at the Tower.

On, or back, to the subject of censorship. Lisa shows us Grace Gifford's cartoon of censor James Montgomery attempting to cover up the Venus de Milo. You will remember that she had two breasts and no arms. Lisa remarked on Grace's treatment of the arms.

Mind you, I've still to see a statue of the Virgin Mary in church where the existence of breasts is even hinted at or her Christmas Eve pregnancy clearly on show. So we can't afford to be too complacent in our looking back.

Gordon Brewster detested Northern Ireland and it reciprocated when one day in Belfast he was picked up by two RUC officers and unceremoniously dumped at the border.

The cartoon above is just one of his many arrows. It shows James Craig, the Norther Prime Minister, pointing a pistol at a Catholic lady bound to a stake. The rub is in the signature: Gordon Brewster after Raemaekers.

I followed that up and there it was, the Raemaekers cartoon he was invoking. Raemaekers was a Dutch cartoonist renowned for his cartoons of German atrocities in Belgium during WWI.

Just as well for Brewster that he didn't "fall down the stairs trying to escape".

So, why am I showing this cartoon which Lisa may never have even seen. Well it's the coverup. We've caught Brewster in a blatant act of censorship. Look closely at the lady in both pictures.

Two photos I can't resist including. Katherine in a state of bliss or ecstasy now that her MoLI is at last up and running.

And Regina, in close up, whom I met in person for the first time though I had previously come across her name all over the place.

This place is where I did my university exams. Today I was back, learning and enjoying myself instead of being tortured to death

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment

Bona fide comments only. Spamming, Trolling, or commercial advertising will not be accepted.