[This section deals with the launch.

I deal more directly with the book itself below].

In his opening words, I think Professor Colm Lennon said it all:

It’s a great honour to have been invited to speak on the occasion of the launch of Peadar Slattery’s Social Life in pre-Reformation Dublin, 1450-1540.

Many years ago I published a book on Dublin in the Reformation period. As I read Peadar’s work, how I wished that it had been available back then, as an invaluable guide to the political, socio-economic and cultural life of late medieval Dublin (that I and others have tried so painfully and inadequately to recreate).

Well, to be fair, there was much more to say, and I won't repeat it all, but it was very positive and coming from Colm was indeed a tribute to Peadar's work. Colm outlined some of the contents, including new material, in the book, but I'll leave you to discover these in the book itself.

I'll just take a few comments which particularly resonated with me.

On the use of sources:

Peadar’s book is based on a range of records that he has mined with great perspicacity – wills, customs and franchise rolls, and official documents of various kinds, for example, – showing what can be done with carefully selected, if limited resources for medieval Ireland.

On standards to which we still aspire in many respects today:

In the sphere of economic life, Peader Slattery has shown that the principle underpinning the regulation of the market and the supply of food and other commodities was based on the maintenance of fair prices and the prevention of profiteering from the sale of produce to which value had not been added in the form of domestic labour.

On identity:

Overall, then, this book not only tells us a huge amount about the formation of a confident, outward-looking urban community of Dublin in the late middle ages, but also raises for modern city-dwellers issues to do with civic responsibility and identity.

It is a tribute to Peadar Slattery’s work that the relevance of the historic to the present is asserted through a myriad of examples and cases.

I urge all here to buy this book and to read it with a view to understanding not just the pre-Reformation city of Dublin but also the timeless urban community values that can and should animate our city in the present day.

You heard the man.

In the course of his reply, Peadar recounted the saga of the book. And particularly the shock at being advised, very late in the day, to extend the period covered up to the Reformation. Medication proved more a hindrance than a help and he just put the head down and got on with it.

By the night, he was able to report this development in a more detached manner:

From the start I had worked with a closing year of 1500, but that year did not make much sense. I wondered should I conclude in 1509, the close of Henry VII's reign. But it was not going to be that easy. In early 2018, both Dr Lennon and Dr Clarke independently suggested that I should continue working out to the 1530s and the early years of the Reformation. A concluding year of 1540 was settled on.He thanked a number of people for varying degrees of help in the writing of the book and in bringing it to fruition. Some of these were present and it must have given them great satisfaction to see the quality of the final product with which they were involved.

Peadar had to pause briefly to collect himself when acknowledging the help of Jane Laughton. Unexpected, but no surprise when you read what he says in the acknowledgements section of the book.

Dr Jane Laughton helped open up a new vista on Dublin-Chester trade in the 1470s, sharing with me her detailed notes on trading between the two cities. Sadly, Jane died in 2017; she thoroughly enjoyed a renewed interest in Chester-Dublin studies. She was scholarly and yet immensely generous with her time and knowledge. I am especially grateful to Jane and her family.This is a very engaging entry on many fronts. It is a terribly sad personal reference at one level, but at another it is testimony to all that is best in the academic tradition - a huge tribute to Jane, and also implicitly to Peadar in whom she placed her trust and who has given us a memorial to her nobility in her last days.

I don't want to overplay this as Peadar has nearly three pages of acknowledgements to people for solid help received in the gestation of this work. But I was touched and encouraged by this reference to Jane. The alligators in the academic swamp are many and voracious.

I get a mention myself in the acknowledgements (thanks Peadar) but was, understandably not alluded to on the night.

So Peadar is now officially a celebrity with an enthusiastic fan following.

You can read Colm's full remarks here and Peadar's full reply here. I'd like to thank both Colm and Peadar for these texts and permission to publish them. They were a great contribution to the night and are well worthy of wider circulation.

Peadar has a short summary piece in the Irish Times.

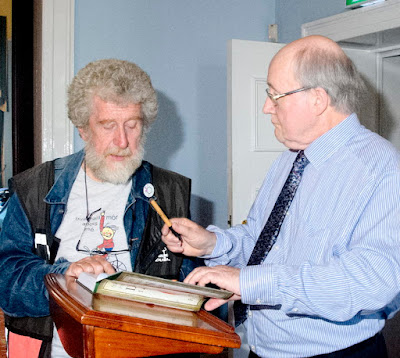

Signing

The usual signing orgy begins

In his acknowledgements, Peadar thanks Professor Fletcher for advice on late medieval drama.

Peter is currently books editor at the Irish Catholic, a title that gives no indication of his vast literary career to date. He was described by the American critic Robert Hogan as “a contemporary embodiment” of the “tradition in Irish literature of the independent scholar, who has an erudition embarrassing to the professional academic”

Alan is a teacher in St. Aidan's. Noel is a TD and former pupil of Peadars.

David was Professor of Astrophysics in UCD and you'll just have to ask Peadar how he fits into the late medieval period. Tommy is related to Peadar.

Leo is Raheny's colourful photographer. He had presented Peadar with an illustrated album of the proceedings almost before the ink was dry.

Unlike myself he is nimble on his feet, or whatever.

Eoin is an IT consultant and latterly also a local history guide. I keep running into him at these types of function.

Attendance

Peter is an urban historian and former curator of the Guinness Museum. Had I known on the night who he was I'd have thanked him personally for a photo of the "Medlar Bridge" he gave me way back through Mary Clarke.

In the acknowledgements, Peadar records his immeasurable debt of gratitude to Professor Clarke and in his remarks on the evening:

Professor Howard Clarke has been very generous with his time, advice and guidance over a number of years and made a most significant contribution to the final shape of this volume.

Ray is Professor of History in Maynooth University and was a colleague in the Department of Finance in the last century.

Brendan Twomey is a retired banker and was awarded a PhD by TCD for a thesis on personal financial management in early 18th century Dublin. The centrepiece of his research was the complex financial affairs of Jonathan Swift. I keep running into Brendan on occasions like these.

Aisling is a history teacher in St. Aidan's.

Sales

For the record, I should state that, despite Peadar's generosity on the night, nobody was observed on this occasion in a "state of inarticulate inebriation", to quote a former boss of mine about a prominent academic at the close of such an occasion.

THE BOOK

There can be no doubting that this is a magnificent work. It fills a gap in research and publication that has deterred many a worthy scholar. Its value lies in giving us a whole picture of the period and bringing it vividly to life for the reader, whether academic or lay.

Peadar has assiduously assembled existing research on the period, directly analysed contemporary records, done his own field work with new discoveries, relentlessly pursued every opportunity to illustrate his material, and finally written it into this wonderful volume. Particular thanks should go to Four Courts Press who have long been champions in publishing such ventures and whose quality standards have been maintained down the years.

A quick reading of the acknowledgements, a ten page bibliography and thirty pages of footnotes will give a a good idea of the breadth and depth of Peadar's journey.

Colm has been very positive in this comments on the book's content and style. I have already linked to his full comments above. In reading these, you can take it that I agree with him entirely.

I will therefore just make a few remarks on things that particularly struck me in reading the book, which I had just finished on the morning of the launch.

When I started into this book, I expected to find a somewhat chaotic Dublin. You know, earlier is primitive, later is more civilised. The idea that the world in general and humanity in particular is on an eternal trajectory of self-improvement/progress. It's the way I was brought up.

So it was a big suprise to discover how regulated the city was in both the areas of commerce and justice. Of course this only applied to those who were entitled to be there. Instant justice dispensed on the spot in the Pie Powder Courts was a discovery. Pie Powder coming from the French pieds poudrés, dusty feet, just in off the street.

It was a very English city and not only had the dispossessed Irish outside to be kept at bay, but, in varying degrees, those Irish within the city were expelled (at various times).

Colm has already commented on the use of sources. I love to see information squeezed out of sources which think they are telling you something else. I'd cite here the examination of wills to identify customers of a business and to show the geographical spread of the business, and its scale. Peadar has specially commissioned maps of the results to illustrate the points more clearly. I've come across nice twists like this before with Cormac Ó Gráda and Anne Dolan, and I love it.

Peadar has gone out of his way to take photos himself to illustrate things more clearly. A good example is the photos of the three Howth Bells (don't mention the metal typo) followed by those of local churches illustrating one, two and two varieties of three bell, belfries.

He got access to, and photographed, a unique Liffey slip-way and he also commissioned the beautiful drawing of the Church St. barn.

I'm mentioning these features to make the point that this book is not just an academic desk job, brilliant and all as that is. Peadar has gone out and done his own field work (literally).

I love this one. Following the fiasco of the crowning of the boy king in Dublin, Henry VII, in 1488, sent Sir Richard Edgecombe to bring the rebel earls into line. He eventually got the earl of Kildare to swear the oath of loyalty to the King not on the bible, but on the consecrated host.

Edgecombe did not trust the Great Earl and when it came to swearing on the Eucharistic host in public at the monastery of St. Thomas the Martyr, Edgecombe ensured that his own chaplain should consecrate the same host on which the earl and lords should be sworn.I think even Dev would have had a job getting round that one.

At a certain point the clergy were seen to be falling behind in their teaching and preaching the core values of the faith. These values were to be found in the aptly named work Ignorantia sacerdotum first promulgated by the Lambeth Council in 1281.

Peadar also alludes to the church peddling (my word, not his) indulgences. These were used to reinforce clerical power and as a source of income. One Papal Nuncio in Ireland even had an income related price list.

Shades of the original version of Planned Giving introduced into the Dublin diocese by John Charles in the 1960s. This version was quickly abandoned following strong protests from the faithful.

Lest anyone doubt my locus standi in these matters I must declare that I was a Latin intoning pre-Vatican II altarboy and my mother sold masses.

Peadar, as befits a teacher, takes the Reformation censors to task for their sloppy work. They were supposed to erase the word Pope from holy manuscripts, as Henry VIII was now head of the English church, and also all references to Thomas à Beckett, whom Henry hated, from anywhere such a reference occurred. While he illustrates their adherence to their instructions in a full colour plate, Peadar draws attention to their actual omissions in the text. Today these fudgings and erasures would be called redactions, and I've seen a fair few botched jobs on this front myself in recent times. But that's another story.

The symbiosis of church and state comes across very strongly. Colm has drawn attention to the citizens' participation in many cross cutting communities. Excommunication could have life consequences as well as those in the afterlife.

Colm mentioned a sense of civic solidarity which made me think of the ambiguity of the Dublin City motto Obedientia Civium Urbis Felicitas, essentially: obedient citizens are a city's joy. However it is not clear how this obedience is to be achieved. You could beat them into submission or look to their needs. Peadar deals with both aspects in the book.

Just on a piece of housekeeping, I have avoided using the term emeritus for retired academics. I'm sure it has its use on formal academic occasions but these guys don't descend into a well of ignorance and irrelevance just because they retire.

I could go on about this provocative book but I'd better stop.